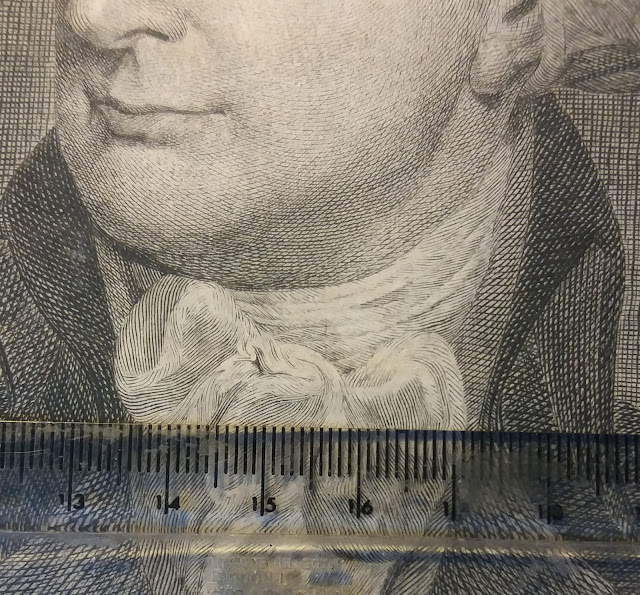

As is well known to Blake students, the artist was apprenticed to an engraver in his mid-teens and maintained a career as a jobbing engraver, which both gave him an income and introduced him to artists and publishers, some of whom became patrons*. Blake’s engraving work on Hayley’s Life of Cowper, published in 1803, was arduous though the results were far beyond competent; rather than thinking of this as drudgery, Blake was pleased with both the work he did and the standard of printing achieved by his wife Catherine – ‘She does [it] to admiration’. Inspection of the print shows Blake’s skill as an engraver, maintaining the curvature of broken line, and using a line of varying width in cross-hatch for nuances of form and tone. He was working at a time when engraving had reached its apogee, before the introduction of Fielding’s parallel line cutting process rendered engraving mechanistic and flat.

With this in mind it is tempting to assume that Blake kept apart the famous relief etching technique, for his own work, and the engraving, for reproducing the work of others. While visiting the recent Blake exhibition at the Tate Modern, at a time when I have been working with both engraving and etching, I spotted an interesting contrast of technique, and one which touches on a longstanding fascination with the reproduction of cross-hatch in printing.

In the title-plate for Chapter 2 of Jerusalem, which he worked on from 1804 till after 1820, two lovers embrace within the blossom of a flower lying on the surface of a pond; a leaf extends forward to the edge of the picture frame. Blake’s standard process in the work is relief etching, painting varnish onto the surface of the copper, and etching the plate in acid to leave a high flat surface which would take the ink from a brayer for contact printing, which water-colour applied afterwards (it is a process which is generally credited to Blake himself). In this image, in the area to the left of the blossom, below the title, there is an area where white line crosshatch lies on a dark background; to achieve the continuity of line (and from the Cowper portrait we can see how important and achievable this was for Blake) there were two possible processes, either to paint in all the intervening lozenge-shaped spaces, or to cut or scribe through a body area of varnish. Surely the second process would have been the instant choice of an engraver; what we do not know though, is whether the cut lines, registering as white, were done by engraving into the plate or just cutting through the varnish. Given the irregularity of the spacing between the lines it was more likely to be the latter. A few centimetres to the right the shading and form of the figure’s clothing is rendered in black line cross-hatch – in this case it is easy to assume the process here was painting the lines in varnish, so that the lozenge/square spaces in between were removed in the etching process. Just above and to the right other shading methods – dot within lozenge, and parallel line – indicate differences of form, texture and tone, both involving the scribe or graver rather than varnishing brush as the mark-making tool.

The leaf that extends to the foreground also shows a range of techniques: to the left black line cross-hatching, and to the right white line hatching. Except that close inspection brings doubt. On the left the lines do not show a continuous flow; it seems to be a net of lines, but some patches of line are thicker than others for very short distances, while others do not match up at all. Here evidently Blake was making the design by the creation of the white spaces between the lines, but how, and why? It is a technique that was used in woodcuts in the 15thand 16thcenturies, and even when Blake started working in wood-engraving in the 1820s he used the by then convention of shading and form though parallel lines rather than cross-hatch. Was he then cutting these, for Blake, irregularly shaped lozenges into the surface with a fine chisel or graver? The right-hand side of the leaf shows a cleaner flow of line, white this time, which would have been straightforward to produce using a soft varnish and a scribing tool. But the central area of the leaf moves, from right to left, from white-line cross-hatch to black-line cross-hatch, with a clear demarcation line where the lozenges change from black to white, and on to white-line parallel lines approaching the central vein of the leaf. Such design choices in such a small area show a mind thinking in advance of the moving scribing tool or graver, creating small areas of detail that indicate Blake working as thoroughly on the detail of composition as on the broad sweep of his spiritual cosmography.

*Proof of how Blake was influenced by the material he worked on as a jobbing engraver can be seen in the poem 'The Fly' in Songs of Innocence and of Experience. Blake supplied engravings for Joseph Ritson's A Select Collection of English Songs (1783), one of which, a drinking song ‘Made extempore by a Gentleman, occasion’d by a Fly drinking out of his Cup of Ale’, supplied Blake with both theme and sentiment.

*Proof of how Blake was influenced by the material he worked on as a jobbing engraver can be seen in the poem 'The Fly' in Songs of Innocence and of Experience. Blake supplied engravings for Joseph Ritson's A Select Collection of English Songs (1783), one of which, a drinking song ‘Made extempore by a Gentleman, occasion’d by a Fly drinking out of his Cup of Ale’, supplied Blake with both theme and sentiment.